As several local leaders participating in a recent resiliency summit noted, people across the region must “dream big” and work together now to mitigate the future effects of a changing climate and sea-level rise.

On June 23, the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council (TBRPC) and the Urban Land Institute of Tampa Bay hosted a four-hour “Resiliency Ready” symposium. During the event, local officials discussed recommendations resulting from three-day charrettes in three study sites representing archetypal flood-prone areas in the region.

The North Tampa Closed Basin represented inland city areas, Pass-a-Grille and St. Pete Beach the region’s barrier islands and R.E. Olds Park in Oldsmar as a waterfront site uniquely susceptible to sea-level rise. St. Petersburg City Councilmember and TBRPC Chair Brandi Gabbard kicked off the event by noting that the symposium was the third major resilience conference in the last three months.

“I always say that we are ground-zero for the effects of climate change,” said Gabbard. “We should be ground zero for the response.”

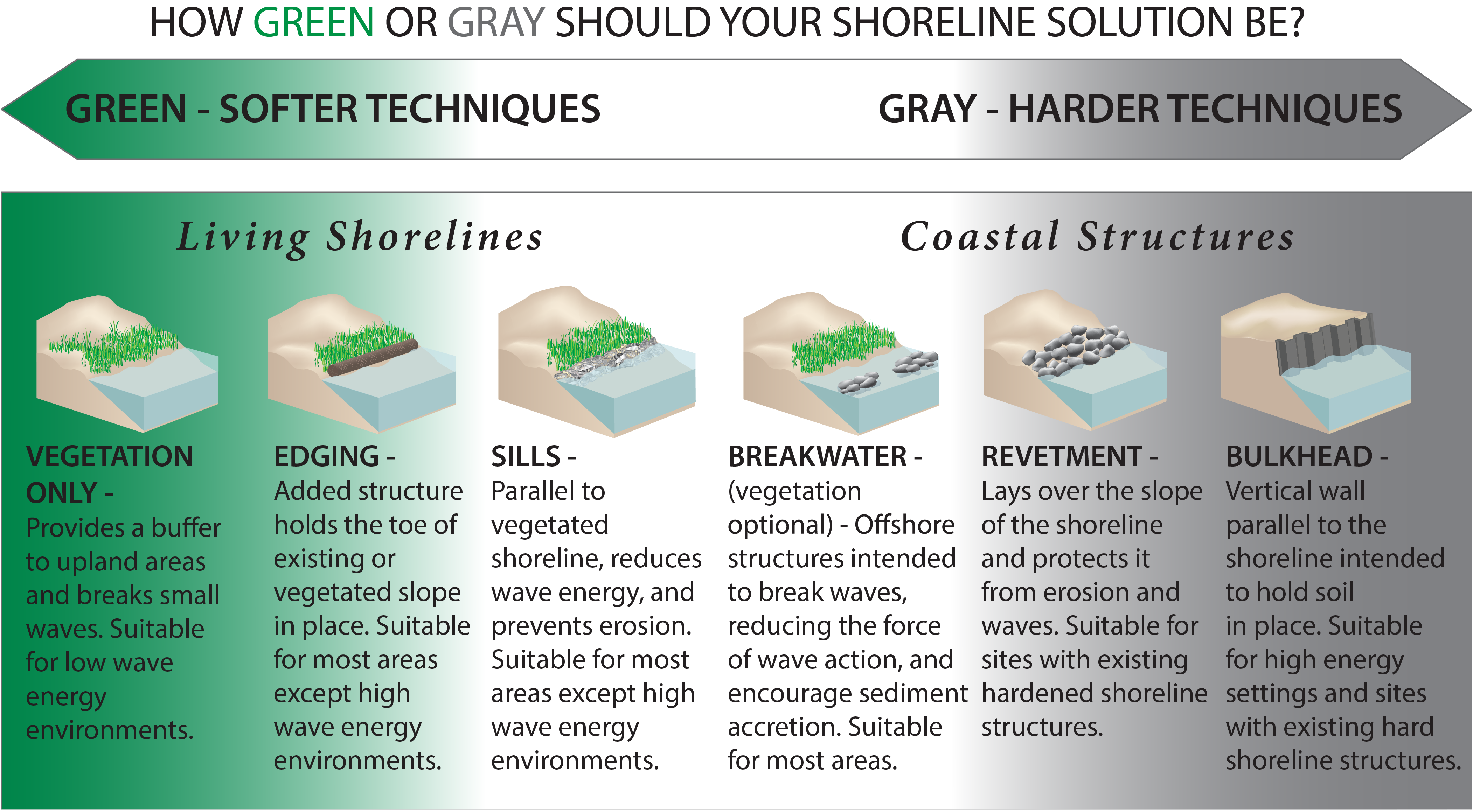

In addition to infrastructure projects, St. Pete Beach is considering green infrastructure initiatives. Those include rebuilding sand dunes, creating offshore jetties to break waves before they hit the shore – and ultimately, the roadways – and planting mangrove trees that can slow water encroachment and act as a natural amenity.

Alan Johnson, mayor of St. Pete Beach, told attendees his city began addressing its climate resiliency several years ago. The city has recently undertaken several roadway and drainage projects and increased seawall height levels. Johnson said incorporating resilience measures into infrastructure upgrades has provided some of the needed funding, but cooperation throughout the entire Tampa Bay area “is essential” to achieving long-term goals.

“You got to realize, we’re fighting mother nature on this,” said Johnson. “I don’t know in the ultimate analysis if we’re going to win this one, but it’s going to be a while.”

In Tampa, plans are underway to transform the area around David E. West Park into a stormwater park system. The project, which Mayor Jane Castor called the “one-of-a-kind” and the largest in North Tampa, will collect and filter stormwater before it reaches the aquifer.

Most importantly, Castor said the stormwater park system would activate and connect the surrounding community.

“And that’s what we really need to do,” said Castor. “Is to look at all of our space and how we can utilize it to its best purpose.”

“What we’ve brought everybody together to do is to dream big and to think of what we can do that is going to be the most impactful in our communities.”

After the symposium, Sean Sullivan, executive director of the TBRPC, told the Catalyst that engaging the public and receiving stakeholder input is critical to the mission’s success. He relayed that a 12 year-old-girl attended one of the charettes and decided to go home and create a logo representing the organization’s seven counties.

Another attendee, said Sullivan, spent her evening after a charette reaching out to neighbors for their thoughts on the North Tampa plan, offering the resulting ideas to her contacts with the city the next day.

“That’s a huge thing,” said Sullivan. “That goes to show that stakeholder engagement, involving the public in the decision-making process and doing it early, can be a success story.”

Sullivan added that incorporating resiliency into municipal projects while in the planning phase gives local officials a competitive advantage when seeking federal funding. Instead of asking “what do I do,” he said going in with a plan featuring resiliency components, and stressing their importance, strengthens the likelihood of approval.

Attendees at the symposium saw an overhead picture of St. Pete Beach from 1926 juxtaposed with one taken recently, illustrating the amount of land the barrier island is losing to the gulf. Similarly, the report states that Oldsmar has a base flood elevation of nine feet, which must increase to over 13 feet by 2070 to stave off rising seas.

While it is the most expensive potential solution, Sullivan said flood-prone areas might have to elevate land and structures.

“So, we learn to live with water,” said Sullivan. “Not only just prevent water from coming into the community but learn to live with it.”

For more information and to view the full report, visit the website here.